Home offices breed a specific kind of frustration: you are reading, coding, or deep in a video call, and the lights click off like the room decided you left. Then comes the shoulder wiggle, the awkward arm-wave, or the chair roll performed solely to keep the lights on. It feels silly, and it breaks focus.

Most people assume this happens because the sensor is “weak” or “cheap.” In desk-bound rooms, the sensor is rarely weak; it’s usually just looking at the wrong slice of the room. The timeout is set for a hallway, but the usage is stationary.

A second problem hides behind the first. If you try to fix it by just “making it more sensitive,” you often trade one annoyance (false-off) for another (random false-on). Pets, HVAC drafts, and ceiling fans start triggering the lights.

A longer time delay and a better “view” usually solve this without turning the office into a haunted room.

The Arm-Wave Problem (And Why It’s Usually Not a “Bad Sensor”)

Desk-bound false-offs follow a pattern. The switch sits by the door, the desk sits deeper in the room, and the sensor’s indicator light happily detects motion—just not from the person at the keyboard. This appears in callback logs so often it’s almost its own category: “office sensor turns off.”

To understand why, picture the wall switch as a camera mounted at the doorway. If that camera points at the empty middle of the room, the door swing, or the hallway, it can be “working” perfectly while still missing the meaningful activity at the desk. A sit-test using the indicator LED reveals this instantly: if the LED barely flickers while you type, the sensor isn’t too weak. It simply isn’t seeing the motion that matters.

People also get tangled up in mode without realizing it. “It turns on when I walk past” is a different problem than “it turns off while I’m working.” Occupancy mode is auto-on/auto-off. Vacancy mode is manual-on/auto-off. In offices—especially those with north-facing windows or partners on different schedules—vacancy mode is often the quiet fix. It removes the irritating false-ons while still preventing an all-night burn.

A longer delay is not a moral failure. In a small room with LED lighting, the cost difference between a 5-minute and a 15-minute timeout is pennies, but the interruption cost is real. A humane delay buys back trust. When people trust the automation, they stop overriding it with desk lamps and workarounds that end up staying on 24/7.

A Quick Mental Model: Treat PIR Like a Camera

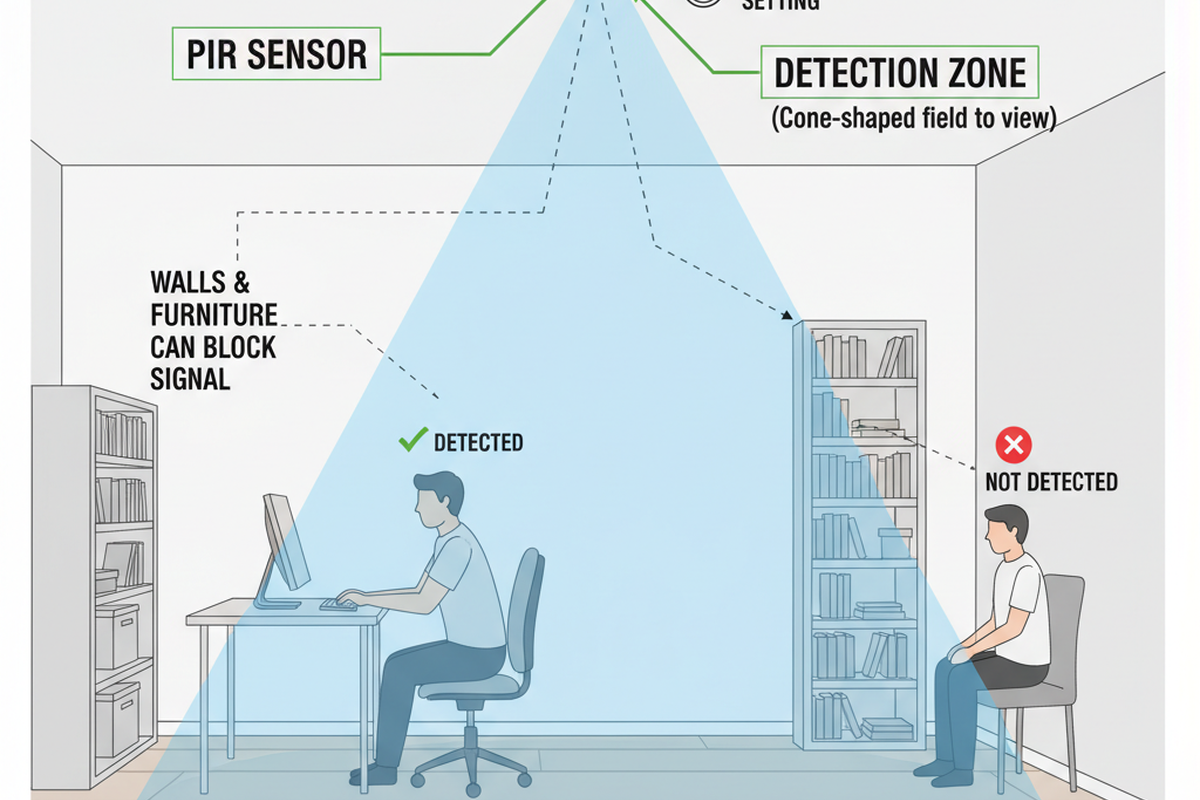

A PIR sensor doesn’t measure “presence” the way a human understands it. It responds to motion in its field of view, specifically motion that crosses its detection zones. Desk work presents a challenge because typing and mousing are tiny movements, often directed toward or away from the sensor rather than across it. Monitors often block the parts of the body that move the most.

Keep the mental model simple: treat the sensor like a camera with a fixed frame. Ask three questions:

- What’s in frame? From the switch’s mounting spot, is the sensor staring at the desk, or over it? Is it mostly seeing the doorway, the hall, or a window with shifting light?

- Does the desk motion register? When you are seated, do your natural movements—hands, shoulders, head—cross the sensor’s “grid,” or do they look like nothing?

- Is the background noisy? Is a fan or heater vent competing for attention?

Don’t touch sensitivity yet.

If you change sensitivity first, you often get rewarded in the worst way: the light stays on longer, but for the wrong reasons. In small rooms with glass doors or corridor exposure, max sensitivity makes the sensor pick up movement that isn’t occupancy. The light becomes chatty, turning on when someone walks by or retriggering when a reflection shifts. If you then increase the time delay to stop the false-offs, those wrong triggers keep the light on even longer. That’s how “fix false-off” becomes “now it’s on all day.”

Maybe You Are Interested In

Keep the problem tight. Change only two knobs at first: what the sensor can see (aim, coverage, placement) and the time delay. Lock everything else for a couple of days. Measure one thing: how many nuisance shutoffs happen per day during real work. Once that stabilizes, sensitivity becomes last-mile tuning rather than desperate guessing.

The 60-Second Sit-Test (Before Buying Anything)

The sit-test is embarrassingly simple, which is why it works.

Sit exactly how you actually work: hands on keyboard, eyes on screen, shoulders relaxed. Don’t “perform motion.” Watch the sensor’s indicator LED. If it barely reacts during normal work, the diagnosis is practically done: the sensor’s frame isn’t intersecting with meaningful motion.

From there, treat the fix like a controlled experiment. Pick two variables to adjust and leave the rest alone:

- The sensing geometry: Aim the sensor down or across the desk plane if adjustable. Avoid aiming into the doorway or hall. If you can mask the coverage pattern, favor the desk and block the corridor.

- The time delay: Choose a starting point that fits cognitive work, not hallway traffic—often 10 to 20 minutes. Adjust based on real annoyance, not theory.

Write down the number of nuisance shutoffs for 48 hours. A sticky note works. You don’t need a spreadsheet; you just need to break the loop of changing five settings at once and learning nothing.

HVAC and fans matter more than people expect. If a register blows warm air across the sensor, or a ceiling fan creates moving thermal patterns, high sensitivity will read that as “motion.” This looks like random false-ons at night or retriggers when the room is empty. Run the sit-test with the fan on and then off, or with the heat cycling. If the sensor behavior changes, don’t crank the sensitivity. Aim away from the vent, narrow the field, and keep the sensitivity sane.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

Once the sit-test shows what the sensor sees, the effective levers become obvious: mode, delay, and geometry. Sensitivity is not the hero of this story.

The Bad Advice Trap: “Just Crank Sensitivity”

The internet loves one-liner fixes, and “turn it up to max” is the most common.

In real rooms, this reliably creates new problems. A glass door facing a hallway makes a high-sensitivity sensor feel haunted. A 35 lb dog moving through the edge of the room triggers it. A ceiling fan or a warm air plume becomes a motion source the sensor can’t ignore. When you eventually extend the time delay to stop the lights from dying, those false-ons keep the system running longer and more often.

The rebuild is boring, but effective: narrow what the sensor can see, put the desk into that view, pick a humane delay, and only then nudge sensitivity if the room is unusually calm. Sensitivity is a finishing touch, not the foundation.

Start-Here Configuration (Office Defaults That Don’t Punish Stillness)

For a typical desk-bound home office with LED lighting (often pulling just 9–12 watts), the goal isn’t maximum theoretical energy savings. The goal is a control system that respects focus and doesn’t get disabled out of spite.

A “start here” configuration that behaves like a human expects looks like this:

- Use vacancy mode (manual-on, auto-off). Essential if the office gets daylight or if the door faces a busy hallway.

- Set a humane delay. Start with 10–20 minutes for quiet work. Shorten it later only if the office proves it can reliably detect seated work without arm-waving.

- Keep sensitivity in the middle. Unless you have a strong reason to change it, leave it alone. In offices with pets or vents, high sensitivity is the fastest route to false-ons.

- Prioritize the desk view. If the device allows masking or aiming, use it to keep cross-traffic out of frame.

This setup is opinionated for a reason: people disable automation they don’t trust. A long delay in a private office isn’t “waste” if it prevents the user from ripping the sensor out or leaving a separate lamp on all day because the overhead is unreliable.

Respect the coupling, though. If the office door opens straight to a corridor, a longer delay can amplify the pain of false-ons. Control the field of view first (what it sees), then extend the delay (how long it stays on). Otherwise, the system becomes generous to the wrong triggers.

Live with the new settings for 48 hours. The room needs time to show its real behavior during actual work, not during a five-minute tweak session.

Troubleshooting Path: If It Still Times Out (Or Starts Turning On Randomly)

If the system still misbehaves, don’t try every setting in the menu. Observe and change one thing at a time.

Confirm detection during the sit-test, adjust geometry so the desk is in view, and extend the delay. If the sensor cannot reliably “see” meaningful seated motion, stop expecting the menu to fix physics.

Occlusion is often the deciding factor. Tall monitors, partitions, and built-in desk niches create dead zones. A wall switch at the doorway may only see the entrance, while you sit in a small cave of cabinetry and screens. In that layout, even a generous 20-minute timeout is just a bandage. The real fix is adding a second viewpoint—often a discreet corner-mounted or ceiling-adjacent sensor aimed across the desk plane. It sounds like “more stuff,” but it’s often cheaper and calmer than endless settings roulette.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

If you are renting or can’t change the wiring, the architecture changes but the goal remains the same. A renter-safe path might be a plug-in lamp on a controlled outlet paired with a better-placed sensor at desk height. The important shift is accepting constraints instead of fighting them with hacks. If you aren’t sure about line-voltage work, hire a licensed electrician. The goal is a reliable office, not a risky DIY story.

If the problem is “it turns on by itself,” treat HVAC and background motion as suspects before blaming the device. Look for vents, fans, or doorways exposing the sensor to heat signatures. Lowering sensitivity and narrowing coverage often improves behavior more than any “micro-motion” setting. Solving false-ons makes it easier to choose a longer delay without feeling like the light is staying on all day for no reason.

If you’re thinking, “Fine, I’ll just buy an mmWave presence sensor,” that can be a valid escalation. But treat it as an escalation, not a default. Presence sensors introduce their own maintenance costs: firmware changes, router reboots, and platform updates. Before adding that complexity, confirm whether a simple vacancy-mode setup plus correct geometry would have solved it. Many “PIR failures” are actually just bad camera angles.

What “Success” Looks Like

Success in a home office isn’t a sensor that impresses guests. It’s a room where you can sit for a long stretch—reading, thinking, typing—and never once notice the lights. The best configuration is the one that becomes boring.

The only metric worth tracking is nuisance shutoffs per day. If it’s still more than zero after a geometry fix and a humane delay, something is still misaligned. There isn’t a universal perfect number for delay; that’s why ranges exist and why a 48-hour trial beats a confident guess.

This guide skips the deep theory of PIR internals and Fresnel lens physics because knowing it rarely changes what fixes a desk-bound office. The practical levers are view, mode, and delay. If those are right and the room still times out, adding a second sensor viewpoint stops being an upsell and starts being the clean fix.