In tropical regions, motion sensors fight a constant battle against the environment. A gecko darting across a wall or a moth crawling on the lens can trigger a cascade of false alarms, leading to wasted energy, frustrated users, and the mistaken belief that the sensor is broken.

It isn’t. The sensor is doing its job perfectly by detecting heat and movement. The problem is that in the tropics, everything is hot and everything moves. The high density of insects and small reptiles blurs the line between a person entering a room and a nuisance trigger. The sensor can’t distinguish between them; both create the infrared signature it was built to detect.

Workable solutions aren’t found in a mythical sensitivity setting or a firmware update. They are found in deliberate mounting choices, physical barriers, and smart maintenance habits. The reality is that you cannot engineer away these environmental factors. You can only manage them through thoughtful installation and realistic expectations.

Why Insects and Small Reptiles Trigger Motion Sensors

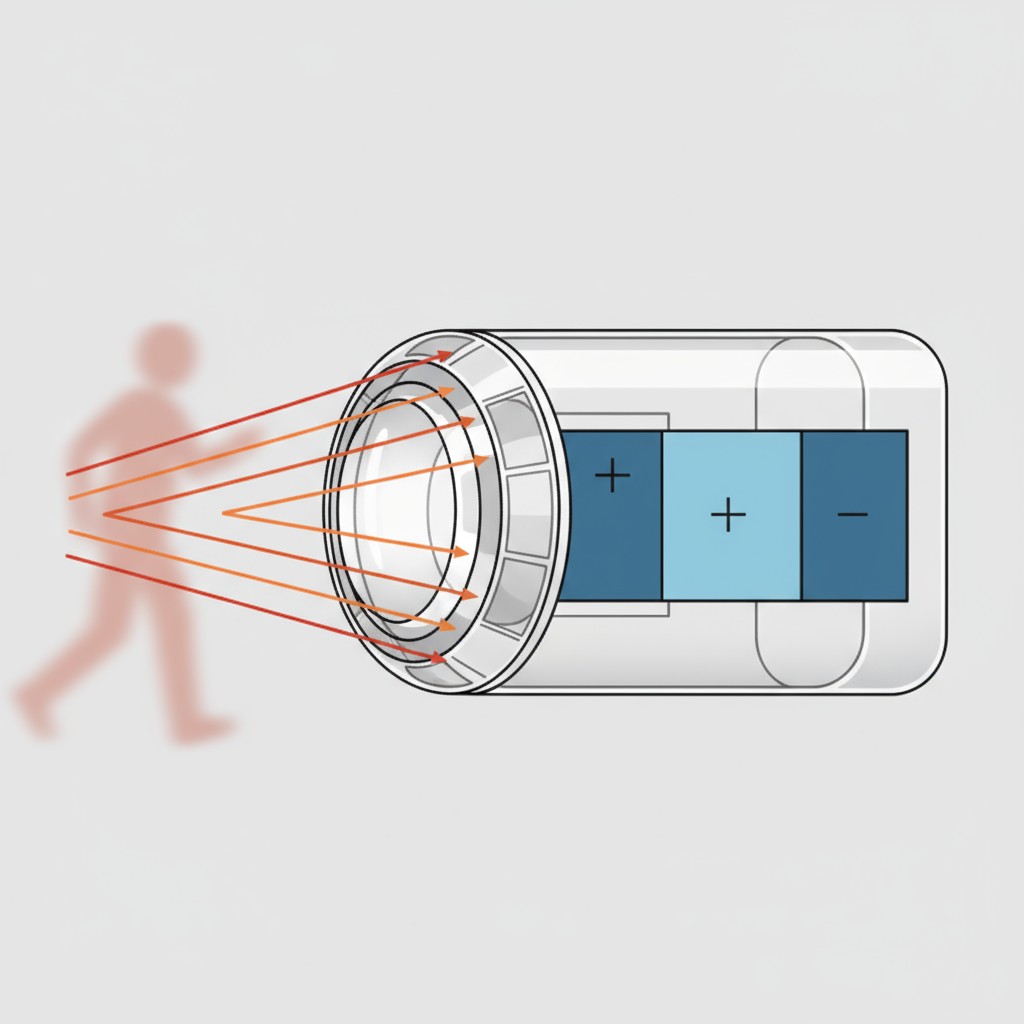

Passive infrared (PIR) sensors work by measuring changes in infrared radiation. The lens focuses heat from the environment onto a pyroelectric sensor divided into zones. When a heat source moves from one zone to another, the sensor registers a differential change. If that change crosses a pre-set threshold, it triggers an alert.

This mechanism doesn’t discriminate. A moth, a gecko, or a human all emit infrared radiation because they are warmer than their surroundings. The sensor only evaluates whether a sufficient change in heat signature has occurred. A large insect crawling directly on the lens creates a massive localized change in infrared intensity. A small lizard darting along a wall generates a moving heat signature that, to the sensor’s logic, mimics a much larger object farther away. Proximity amplifies the apparent size of the heat source, so a beetle just one inch from the lens can create an infrared signature comparable to a person walking ten feet away. The sensor has no way to interpret distance or scale; it just responds to the physics of the infrared differential.

Heat Signature Detection in Tropical Conditions

Tropical environments compress the thermal range between the ambient background temperature and living organisms. In a temperate climate, a 70°F room and a 98°F person present a clear 28-degree differential. In a tropical home where the ambient temperature might be 85-90°F, that differential shrinks to less than 15 degrees. To reliably detect humans in this narrow range, the sensor must be more sensitive. This increased sensitivity, however, makes it far more prone to triggering on smaller heat sources that would be ignored in cooler climates.

High humidity further complicates detection, as water vapor absorbs and scatters infrared radiation, creating an unstable thermal background. The sensor constantly recalibrates to this shifting baseline, where any movement, even a fly crossing the lens, can register as a significant event. Add to this an insect density that is orders of magnitude higher than in temperate zones, and false activations become a predictable, recurring condition.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

Insect Crawls Versus Lizard Movements

Insects crawling directly on the sensor lens cause the most dramatic false triggers. A moth or beetle millimeters from the pyroelectric element generates an infrared spike that blasts past the activation threshold. Crawling insects also tend to linger, causing repeated triggers as they shift position.

Lizards and geckos create a different signature. They move in short, rapid bursts along walls or ceilings within the sensor’s field of view. Their movement speed and size fall squarely within the range the sensor is designed to detect. Unlike an insect on the lens, a lizard is a legitimate moving heat source within the detection field—it’s just not the intended target. This distinction is crucial for mitigation. Insect crawls can be stopped with physical barriers, but lizard movements require smarter mounting strategies. The challenge isn’t a broken sensor, but a mismatch between the technology and its environment. Fortunately, this mismatch can be managed with intelligent installation.

Mounting Height and Angle Reduce Crawler Access

The single most effective way to reduce insect-related false triggers is to mount the sensor where crawling insects can’t easily reach the lens. This is a permanent, zero-maintenance solution that addresses the root cause of the problem.

Maybe You Are Interested In

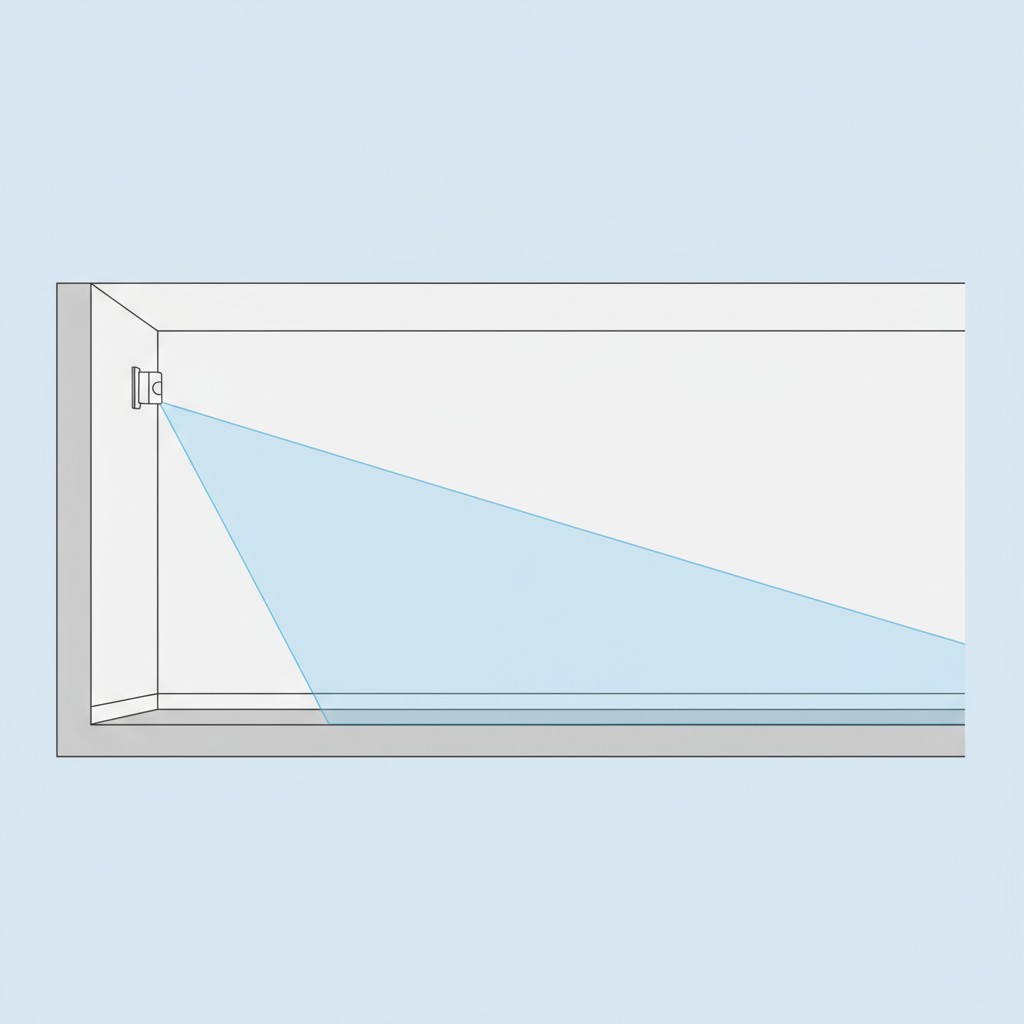

- Optimal Mounting Height: Position wall-mounted sensors seven to nine feet above the floor. This places the unit above the primary pathways for crawling insects, which tend to be near the ground or around mid-wall fixtures, while still reliably detecting human movement below.

- Downward Tilt: Angle the sensor downward by five to fifteen degrees. This directs the detection field toward the floor, where people are, and away from the ceiling, where lizards and insects roam. It also makes the top of the housing less horizontal, discouraging insects from landing and resting on it.

- Corner Mounting: Insects that follow walls often get lost at inside corners. Mounting the sensor in or near a corner disrupts the continuous surface path an insect can follow to reach the lens, making it particularly effective against ants and beetles.

- Ceiling Mounting: In spaces with high ceilings, a ceiling-mounted sensor can work if its detection pattern is narrow and tightly focused on the floor. This advanced strategy requires a sensor with an adjustable or interchangeable lens to exclude the ceiling plane from the active field.

Physical Barriers Outperform Settings Adjustments

The first instinct when facing false triggers is to dial down the sensitivity. This approach is appealing because it requires no tools, but it’s also largely ineffective. Sensitivity settings adjust the trigger threshold, but they can’t teach a sensor to distinguish a moth from a person. An insect crawling on the lens creates such a massive infrared signature that even the lowest sensitivity setting will see it.

Physical barriers are far more effective because they remove the problem from the sensor’s environment entirely.

- Lens Shrouds and Directional Shields: Shrouds are tunnel-like extensions that create a physical labyrinth crawling insects cannot easily navigate. Directional shields use angled baffles to block line-of-sight access to the lens, deflecting insects away from the sensitive surface.

- Aftermarket Guards and Mesh Screens: For sensors without built-in protection, a fine stainless steel mesh (with a grid size of about one millimeter) can be installed over the lens. The mesh is fine enough to block insects but open enough to allow infrared radiation to pass through, preventing direct lens contact without impeding detection.

These barriers are passive, reliable, and mechanical, not algorithmic. Reducing sensitivity or range enough to stop insect triggers often means the sensor will also miss legitimate human activity—creating a different kind of failure. There is no magic setting that allows a sensor to distinguish a beetle on the lens from a person across the room.

Ambient Light Thresholds Limit Nighttime Nuisance Triggers

Most motion sensors include a photocell that only allows activation when light levels fall below a set threshold. This feature is designed to save energy during the day, but in the tropics, it serves another critical function: decoupling the sensor from peak nocturnal insect activity.

Nocturnal insects are drawn to light, including the small indicator LEDs on sensors. By setting the ambient light threshold to disable the sensor during full darkness, you can eliminate an entire category of false triggers caused by moths and beetles attracted to the device at night. This approach is a complementary tool, not a replacement for physical barriers or proper mounting. When used in combination with other strategies, it can significantly reduce the total number of false trigger events.

Maintenance Habits That Matter More Than Mythical Settings

A perfectly installed sensor will still fail if it isn’t maintained. In humid environments, organic residue, dust, and insect debris quickly accumulate on the lens. This buildup doesn’t just block detection; it actively causes false triggers.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

- Insect Residue: Insects leave behind oils and fragments that form a film on the lens, scattering infrared radiation and creating erratic triggers.

- Mold and Organic Growth: In high humidity, mold can grow on the sensor housing and near the lens, creating its own localized heat signatures.

A sensor in an insect-heavy environment should be visually inspected every two to four weeks. If the lens isn’t perfectly clear, it needs cleaning. Wipe the lens and housing with a soft, lint-free cloth dampened with isopropyl alcohol. Check that all seals on the housing are intact to prevent insects from getting inside. The return on this effort is high. Regular maintenance is the difference between a functional installation and an abandoned one.

Accepting Trade-offs and Setting Realistic Expectations

Even with perfect mounting, barriers, and maintenance, some false triggers are unavoidable in environments with extreme insect density. The sensor’s fundamental principle—detecting infrared change—cannot be redesigned to ignore all non-human heat sources without also ignoring humans.

The goal is not zero false triggers. The goal is a false trigger rate low enough that the sensor still provides net value in energy savings and convenience. A sensor that triggers once or twice a night from a gecko but reliably detects people is still a success. However, if false triggers become frequent enough to be a constant nuisance, it may be time to reconsider the sensor’s placement or switch to a different technology, like a dual-tech sensor that requires both PIR and microwave detection simultaneously.

For tropical installations, success comes from prioritizing physical solutions over chasing mythical settings, committing to regular maintenance, and understanding that the sensor is responding correctly to the environment it occupies. The environment, not the sensor, is the variable that must be managed.