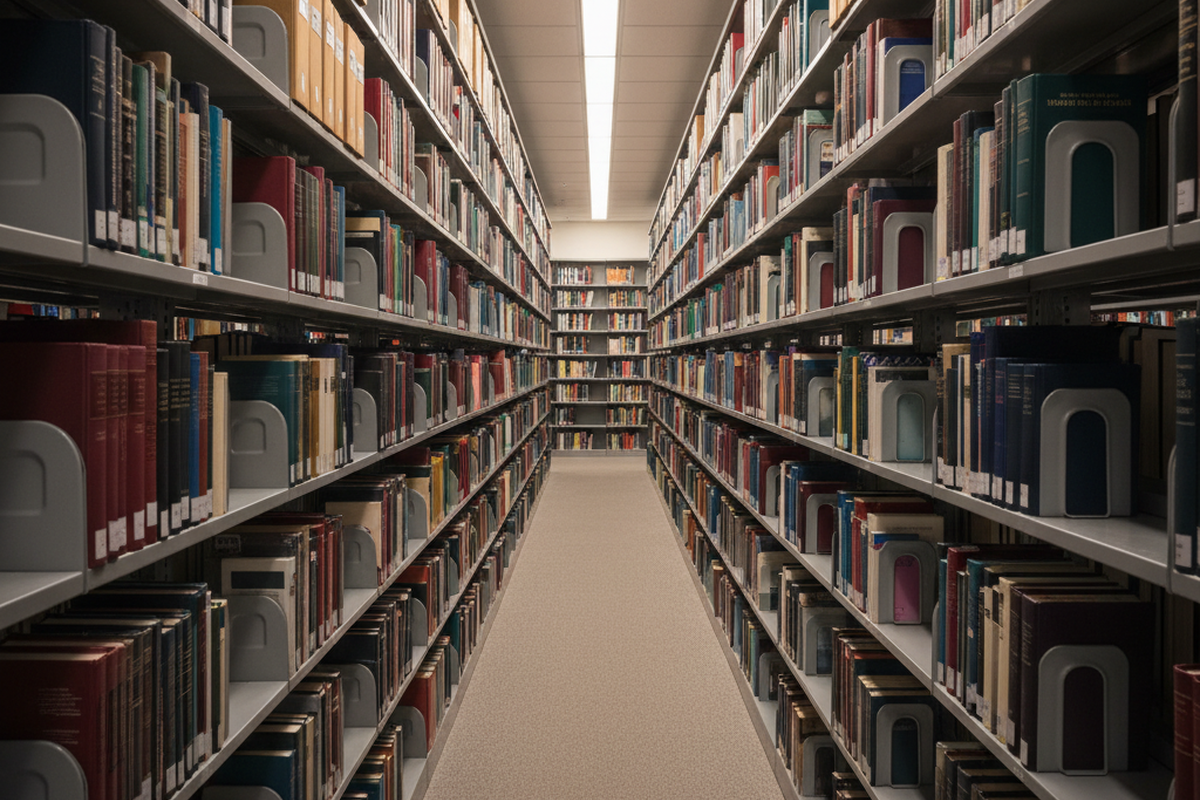

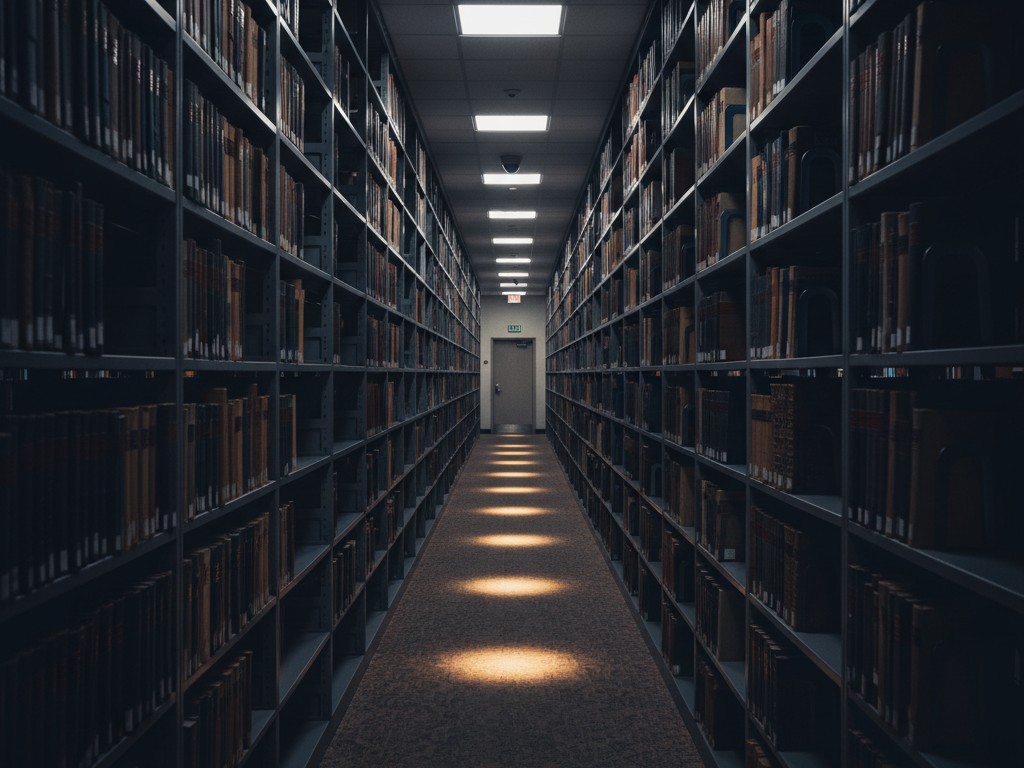

Walk into the deep stacks of a university library or a county archive basement, and the sensory experience is often immediate and hostile. There is a hum, perhaps the buzz of aging magnetic ballasts, but more palpably, there is the “tunnel effect.” You stand at the head of a 40-foot aisle, flanked by towering metal shelves, looking into a cave. If the facility is older, the light is yellow and dim, pooling on the floor while the top shelves disappear into shadow. If it has been “modernized” cheaply, you get a harsh, blue-white interrogation glare that snaps on only when you are three feet into the darkness.

This isn’t merely an aesthetic failure. It is functional hostility. Patrons describe the feeling of being watched, or the anxiety of lights timing out while they are mid-search. For the facility manager, these complaints are often treated as noise in a system demanding aggressive energy reduction. But treating a library stack like a warehouse aisle is a fundamental error in design logic. Humans scanning book spines have optically distinct requirements from forklift drivers reading pallet labels. Ignoring that distinction is why so many retrofits fail.

The Floor Is Not the Task

The most pervasive error in stack lighting is the obsession with horizontal illuminance—light hitting the floor. In a standard office or reading room, code compliance often dictates an average of 30 to 50 footcandles on the “workplane,” usually a desk height of 30 inches. In a stack, the floor is irrelevant. Patrons do not read the carpet.

The “workplane” in a library stack is a vertical surface stretching from six inches off the floor to seven feet in the air. This presents a brutal geometric challenge. A light fixture mounted in the center of a narrow aisle is naturally inclined to blast light straight down. This creates a “hot spot” on the top shelf—often so bright it causes glare on glossy dust jackets—while the bottom three shelves languish in deep shadow.

A proper audit of a stack environment requires a shift in metrics. You must measure vertical illuminance at three points: the top shelf, the middle, and the infamous bottom shelf. The goal is uniformity. The Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) RP-4-20 standard provides guidance here, but the practical reality is simpler. If the ratio between the brightest point on the top shelf and the darkest point on the bottom exceeds 6:1, the human eye struggles to adapt. The bottom shelf becomes a black hole. When reviewing a lighting plan, if the engineer speaks only of “average room lux” without showing a vertical calculation grid, the design is already broken.

Maybe You Are Interested In

Optical Control: Bending the Beam

Solving the vertical problem requires optics, not just raw power. This is where the difference between a purpose-built library fixture and a generic “strip light” becomes painful. To light a vertical shelf evenly from a central overhead position, the light must be thrown sideways, not down.

This requires a double-asymmetric lens distribution—often referred to as a “batwing” optic, though true stack lights have a much more aggressive angle of attack. The lens captures the photons that would naturally hit the floor and refracts them high and low onto the shelf faces. A high-quality stack fixture might actually appear dimmer when looking directly up at it because the light is being harvested and redirected to the spines.

There is a temptation, driven by budget committees and energy audits, to bypass new fixtures entirely and simply install LED tubes (TLEDs) into existing fluorescent housings. This is almost always a mistake in a stack environment. The existing housing was likely designed for an omnidirectional fluorescent tube. Replacing it with a directional LED tube destroys whatever crude optical control the original fixture had. The result is often a “zebra striping” effect: bands of shadow and light that significantly increase glare. The housing matters more than the diode. Without the correct lens to push light to the bottom shelf, energy savings come at the cost of usability.

The Anxiety of the Timer

If optics define visual quality, controls define emotional safety. The most common complaint in modern archives is the “waving arms” phenomenon. A researcher, seated on a step stool in the middle of a long aisle, is reading a text. Because they are relatively still, the motion sensor—usually a passive infrared (PIR) unit mounted at the end of the aisle—assumes the space is empty. The lights plunge into darkness. The researcher, terrified and blinded, must stand up and wave their arms to re-trigger the sensor.

In a warehouse, this is an annoyance. In a public library basement, it is a liability. The issue lies in the sensor technology. PIR sensors rely on line-of-sight and significant movement. In the “metal canyons” of compact shelving, line-of-sight is easily blocked by the shelves themselves.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

The solution is Dual-Technology sensors, which combine PIR with Microphonic or Ultrasonic detection. These sensors can “hear” or “sense” small movements—the turning of a page, the shifting of weight on a stool—around corners where the infrared beam cannot see. They maintain presence detection long after a standard sensor would have timed out.

Furthermore, the logic of “100% Off” needs to be challenged. While energy codes (like IECC or ASHRAE 90.1) push for aggressive shut-offs, the psychological impact of walking into a pitch-black aisle is severe. It triggers a primal avoidance response. A more humane approach is “background tuning” or a “dim-to-warm” state. When an aisle is vacant, the lights should fade to 10% or 20%, not zero. This maintains a visual rhythm in the space, preventing the “cave” effect, while still harvesting the bulk of energy savings. The cost of that last 10% of electricity is negligible compared to the cost of a student feeling unsafe enough to stop using the stacks.

Wireless controls (like Lutron Vive or similar mesh networks) make this granular control possible in retrofits without running new data wires, though they introduce a maintenance layer—batteries. Facility teams must weigh the trade-off of changing sensor batteries every five years against the impossibility of rewiring a concrete ceiling.

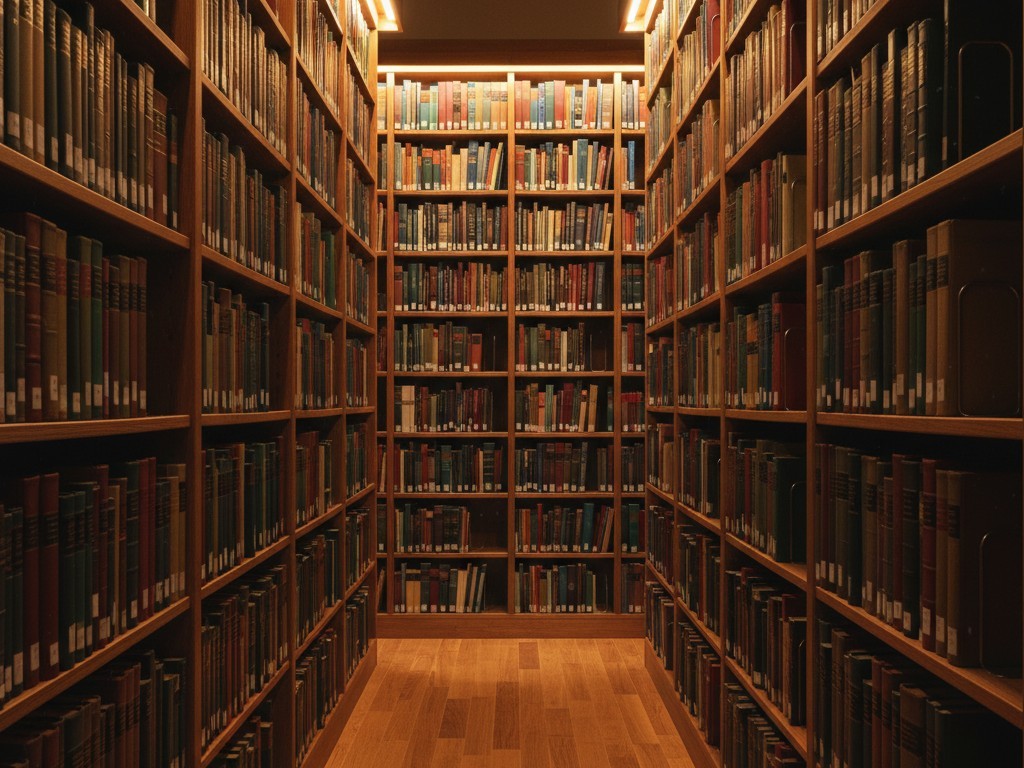

Spectral Integrity and Preservation

Then there is the matter of the light itself—specifically, its color and its safety for the collection. Archivists often fear LEDs, citing “blue light hazard” or UV damage. Modern high-quality LEDs, however, produce virtually zero UV radiation compared to the fluorescent tubes they replace, which were notorious for pumping out UV spikes that faded spines. The danger with LEDs is not UV, but the “blue pump”—the spike of blue energy used to generate white light.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

Cheap, high-Kelvin (5000K or “Daylight”) LEDs have a massive blue spike. This high-energy wavelength is the most damaging part of the visible spectrum for paper and pigments. It also renders the library with the sterile, clinical pallor of a morgue. For collections involving rare maps, leather bindings, or color-coded archives, the metric to watch is not just CRI (Color Rendering Index), but specifically the R9 value (red rendering).

Standard 80 CRI LEDs often have a negative R9 value, meaning they mute reds and browns—the exact colors of old books and wood shelving. A 3000K or 3500K source with a CRI of 90+ and a positive R9 value is not a luxury; it is a preservation tool. It minimizes the blue spectral peak while allowing the true colors of the collection to be distinguished. If a contractor suggests 5000K tubes to “brighten up the place,” they are prioritizing perceived brightness over the chemical stability of the collection.

Conclusion

We treat libraries as repositories of data, but they are physically inhabited spaces. The lighting must serve two masters: the preservation of the object and the comfort of the human finding it. When we chase the lowest possible wattage or the cheapest retrofit kit, we fail both. We create spaces that degrade materials through poor spectral management and degrade the user experience through gloom and anxiety. We aren’t just lighting a room. We’re lighting vertical spines—safely and warmly—so users actually want to stay.