A common split-level scene looks boring until it doesn’t. Someone comes up from a finished basement, hits the landing, pivots with a foot on each level, and the stair light snaps off, then back on, then off again. The complaint that follows is almost always phrased like a device problem: “It’s not sensitive enough,” or “It’s flickering,” or “This sensor is junk.”

But on split-level stairs, the landing is the trap. The geometry and the way people actually move—boots in winter, hands full of groceries, a pause to turn—breaks the default assumptions most PIR wall switches make, especially at a 30‑second factory timeout.

The light should stay ahead of you.

The fastest way to waste a weekend is chasing “more sensitivity” as the first fix. Detection range is rarely the failure. The real issue is what happens when motion stops for two seconds in a spot where the sensor can’t see a torso. If the homeowner’s trigger phrase is “sensor misses me when I stop,” that is the hint to adjust the hold time and line-of-sight before touching sensitivity. Split-level stairs punish twitchy timing. They also punish a sensor aimed straight down a stair run that only sees shins from one direction.

When people say “strobing,” it helps to define terms before replacing fixtures. In a 1994 tri-level, a phone video of an on‑off‑on pattern right at the landing looked like flicker, but it tracked the person’s pivot perfectly. The LED driver responded to rapid power cycling, but the cause was control behavior: short delay, awkward retrigger logic, and a landing pause that created a dead zone. If the on/off events line up with the steps and the pivot, treat it as control flutter tied to movement patterns. The wiring usually isn’t haunted; the staircase is exposing timing and coverage mistakes.

What a PIR Is Actually Doing on a Landing

A PIR wall switch doesn’t read minds, and it doesn’t measure “occupancy” the way people use the word. It watches for changes in infrared patterns across its window. On a straight hallway, that works well because motion is continuous and mostly perpendicular to the sensor’s view.

On split-level stairs, the route changes: approach from the basement or main floor, pause at the landing, pivot, then continue. That pause is the key. The switch sees motion (trigger), starts its hold time, and applies internal rules about retriggering. If the hold time is short and the sensor has a dead spot during the pause, the light cuts out while the person is still on the stairs. The pivot creates motion again, so the light pops back on. That’s the “strobe,” and the stairs are doing it on schedule.

This is where people get annoyed: short timeouts are marketed as efficient, but on stairs, they’re a bad trade even before safety is mentioned. In a 12‑unit condo stairwell after an LED retrofit, shaving minutes off the on-time barely moved the electricity bill. It did, however, spike the complaint volume. Residents stood still with keys and packages, plunging into darkness because someone insisted on aggressive shutoff. Once the timeout pushed into the 5–10 minute range, tickets dropped to near zero. On modern LED stair fixtures, the “energy savings” argument for a 30‑second timeout collapses in real life. The stair circuit is low wattage; the human cost is not.

Maybe You Are Interested In

A quick diagnostic check keeps this from turning into guesswork. If the “flicker” happens even when the switch is steady-on—no motion events, no click on/off sequence—then it may be an electrical/driver compatibility issue. But if the on/off pattern lines up with the landing pause and the pivot, treat it as timing and coverage first. A lot of fixture swapping happens because the label “strobing” suggests hardware failure, when the behavior is really trigger → hold → retrigger interacting with the route.

The Field Guide: Make the Stairs Boring (in a Good Way)

Don’t judge a stair sensor by waving your hand in the air. Judge it by walking the route. Walk from the basement to the main floor and back, at normal speed. Do it again carrying a laundry basket. Pause on the landing for 2–5 seconds like a tired person would. If it is winter, imagine boots and a slower pivot; in a 1989 split-entry, that “I’m just turning around” pause is where the 30‑second default setting punishes people. The goal is simple: the light comes on early enough, stays on through the landing pause, and doesn’t turn into a jumpy assistant when the motion changes rhythm.

What not to do, because it shows up in service calls and homeowner texts over and over:

- Set a 30‑second timeout on stairs and call it “efficient.”

- Aim the sensor straight down the stair run and hope the landing takes care of itself.

- Max out sensitivity to fix misses and then act surprised by 2:13 a.m. false-ons.

- Mix two random “smart 3‑way” kits from different brands and expect predictable states.

Better devices aren’t magic, but cheap behavior is expensive. Feature shopping should focus on how the device acts, not the detection cone diagram. A useful stair sensor gives a real timeout range that can be set long (minutes, not seconds) and has stable retrigger behavior so the light doesn’t drop out during a pivot. It should have a clear mode choice—occupancy vs vacancy—so the household isn’t accidentally living with a setting nobody intended.

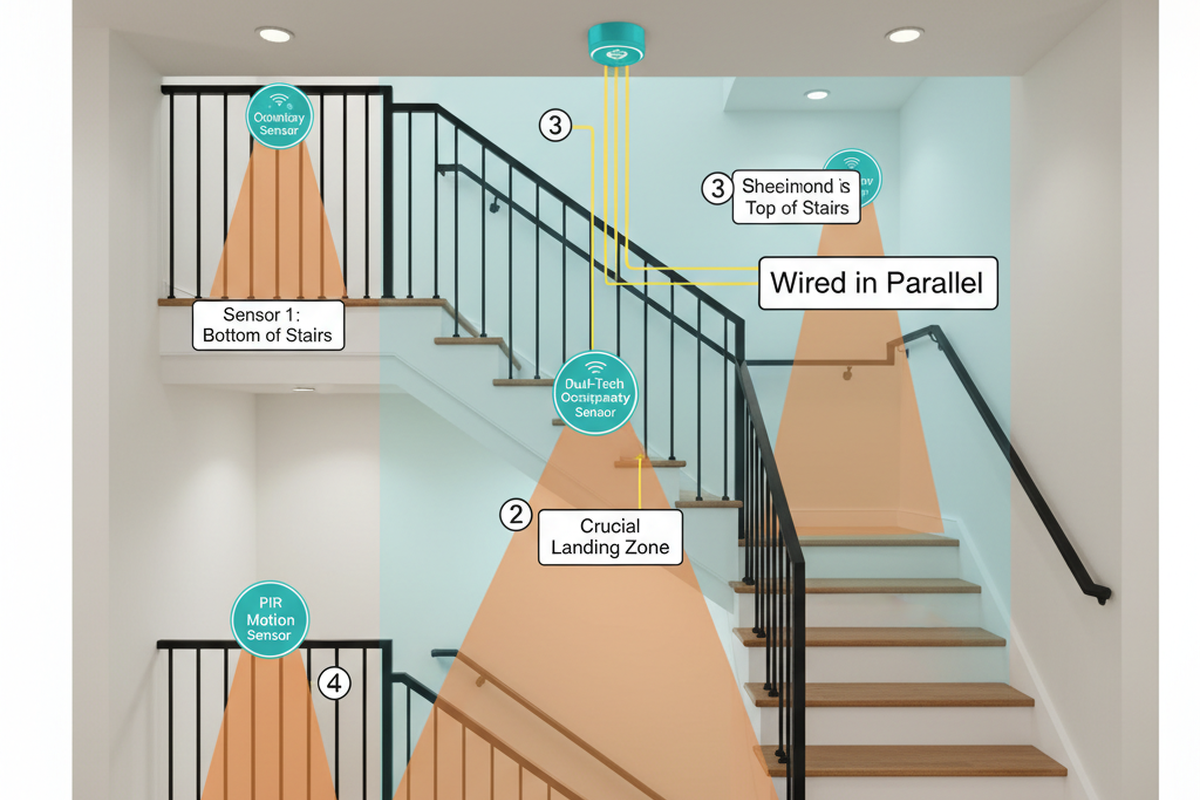

If the stairs have multiple locations (bottom/landing/top), the sensor should belong to a matched multi-location system: one master sensor/dimmer/switch and the correct companion(s), not a pile of “3‑way compatible” claims. Contractors stock lines like Lutron Maestro or Leviton Decora for a reason: fewer weird behaviors, clearer multi-location options, and fewer callbacks. That bias exists because it works. The goal is a setup people stop thinking about, not one that looks clever on a spec sheet.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

Placement and aim do more work than sensitivity, especially on landings. The most common stair mistake is placing a sensor where it only sees one approach and only sees legs. A landing is a pause point and a two-direction approach point. If the sensor is blinded by glare from a bright LED fixture, or staring down the run, it will miss the part of a person that stays still during a pivot.

Cross-traffic coverage is the default recommendation: aim so the sensor sees a torso moving across its field as someone enters the landing, not just a foot moving up a tread. In a 2021 house with cats and a supply vent pushing air across the sensor field, the “fix” wasn’t higher sensitivity. That just created midnight false triggers. The calm fix was backing off sensitivity, increasing the timeout, and aiming for human movement patterns rather than the vent stream.

Night routines change the definition of “good.” Some households want the stairs bright at 6 p.m. and gentle at 2 a.m. Others want vacancy-only at night because a motion pop-on wakes kids or a night-shift worker. That preference is legitimate, but it increases the need for stable timing and a clear manual option. If the stairs are too bright at night, shortening the timeout until the landing goes dark mid-step isn’t the answer. The solution is usually a night-level/dim strategy, a separate low-level path light, or a mode choice the household understands. The route still has to stay lit.

People underestimate the manual override. There needs to be an “always-on” behavior for parties, moving furniture, sick nights, or a week when the sensor is acting up. If the only way to get that is hunting through an app, the lighting feels hostile to guests. The practical goal is an obvious, physical override at the most-used entry point—often the garage-to-basement door in a split-level—so the household can force steady light without a lecture. When that override exists, people tolerate sensors again because they aren’t trapped.

Multi-Location Stairs: The System Design People Skip

Multi-location stairs break the most DIY plans. A three-way label on a box does not mean two devices can be swapped in independently. On stair runs with multiple control points, the household relies on predictability. If one location behaves like a true toggle, another behaves like a momentary companion, and a third is a “smart add-on” with its own rules, the system creates state confusion. On a landing, state confusion is almost as bad as darkness: people reach for a switch out of habit, get an unexpected result, and start doing unsafe workarounds like walking faster or leaving lights on all day.

The wiring reality is part of why this is hard. In older 1978–1984 era homes, it’s common to open a box and find no neutral because of a switch loop. That immediately narrows which devices work at that location, often forcing the “master” to live in a different box than expected. This is where “just buy two motion sensors and put one at each end” becomes a trap. Treat the wall as one coordinated control system, not a pile of switches.

Old-Work Reality Check (Before Buying Anything)

Retrofits survive on three unglamorous questions: is there a neutral in the box, how is the multi-location wiring actually arranged, and is there enough space in the box for the device and conductors? In many split-levels with existing 14/2 and 14/3 runs, the neutral isn’t where you want it. The homeowner plans to “swap the stair switch,” but the open box reveals a switch loop: hot down, switched hot back up, no neutral bundle. That’s not a moral failure; it’s old-work reality. It’s also why some devices that look perfect online are dead on arrival in a specific wall.

A practical set of options usually exists, but it changes with access.

- Choose a sensor that does not require a neutral in that box.

- Move the “smart” part of the control to a location that does have a neutral, and use a companion elsewhere.

- Do the work at the fixture/ceiling box if accessible, where neutrals are often present.

- Sometimes the real option is timing: if a remodel is coming, pull the right cable then. Fishing in a pristine finished stairwell is where budgets and patience go to die.

Decide based on topology, not wishful thinking.

There is also a line where DIY confidence should turn into professional help without shame. If the box is crowded (box fill), if there are multiple gangs with shared circuits, if travelers aren’t obvious, or if someone is not comfortable verifying power-off and tracing conductors, it is time for a licensed electrician. Stairs are not the place to “figure it out live” at 9 p.m. on a Sunday. A careful pro will map the circuit, label travelers, and make sure the system behaves consistently from every entry point.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

One more honest uncertainty deserves daylight: local code expectations and inspection habits vary by jurisdiction, and product lines change year to year. Treating internet wiring advice as universal is risky. The stable move is to read the current manufacturer installation manual for the exact device family being used, confirm what it requires (neutral, companion type, allowed wiring methods), and when in doubt, pull in licensed help. Feature-based requirements age better than SKU claims.

Troubleshooting: A Calm Sequence That Matches the Stairs

Troubleshoot the staircase, not the datasheet. Start with the route-walk simulation: walk the stairs from both directions, hands empty, then hands full (groceries, laundry basket). Pause on the landing for 2–5 seconds. Watch whether the on/off events track the movement pattern. If the light goes dark during the pause, increase the timeout first. If the light misses from one approach, look at placement and aim before sensitivity. If the behavior looks like on‑off‑on right at the pivot, treat it as hold/retrigger logic interacting with the pause. This is the same pattern that shows up in those “strobing” videos in tri-levels with LEDs: the driver reacts, but the cause is timing plus coverage.

Then address false triggers with the same calm logic. If the complaint is “it turns on at night” or “it’s haunting us,” assume the sensitivity tax is being paid. Check for HVAC vents pushing air across the sensor’s field, ceiling fans near the stairwell, and pets that like the landing rail. A supply vent crossflow plus high sensitivity is a predictable 2 a.m. story, not a mystery. Back off sensitivity, increase timeout, and re-aim toward human cross-traffic. The stairs need calm, not twitch.

The final measure of success is boring: nobody changes their behavior to accommodate the light. Kids don’t run the stairs because they’re racing a timer. An older adult doesn’t hesitate on the landing because they’re afraid it will go dark. Guests don’t hunt for an app to force the light on. If the system keeps light ahead of the route, and there is an obvious manual override when life gets messy, the “smart” part disappears—and that is the win.