The psychological weight of a dark basement isn’t about ghosts or childhood fears. It is a rational response to a lack of visual data. When we stand at the top of a stairwell looking down into a void, the brain signals danger because it cannot verify the integrity of the surface we are about to step on.

In older homes—particularly the split-levels and colonials common in the Midwest and Northeast—this “black hole” effect is usually the result of a single, inadequate light source triggered by a switch that is impossible to reach without descending into the dark first. We see the consequences of this design failure not in ghost stories, but in urgent care visits for compounded fractures and severe sprains.

The fear is often compounded by the “sprint” reflex. Even rational adults will find themselves hurrying up the last three steps of a basement staircase, propelled by a lizard-brain impulse to get back to the lit kitchen. This isn’t paranoia; it is a reaction to contrast. When a basement is poorly lit, the eye struggles to adjust between the bright safety of the upper landing and the murky gloom of the lower steps. We don’t need bravery. We need to engineer the environment so the path is fully illuminated before the door even opens, removing the biological trigger for fear entirely.

The Physics of the Shadow Trap

Most residential stairwells suffer from a fundamental flaw in fixture placement that creates a “shadow trap.” In a standard builder-grade setup, a single overhead light is often mounted halfway down the stairwell or, worse, on the ceiling of the basement proper. As you descend, your body blocks the light source from above, casting a sharp, dense shadow onto the treads in front of you. You are effectively blinding yourself with your own silhouette. This self-shadowing hides the edge of the tread, making it impossible to gauge depth or distance accurately.

To eliminate the shadow trap, treat light as a fluid that needs to wash over the surface, rather than a beam pointing at it. The Illuminating Engineering Society (IESNA) standards for stairwell uniformity suggest minimizing the contrast ratio between the brightest and darkest points on the treads. Achieving this usually requires light sources that originate from in front of the user during descent, or a high-output wash that bounces off the walls to fill in the shadows. When the light comes from the wrong angle, a toy truck left on the third step becomes invisible until it is underfoot.

This is where the “contrast ratio” becomes the true enemy. A single, bright bulb at the bottom of the stairs actually makes the descent scarier. It causes the pupil to constrict to handle the hot spot of light, crushing the perceived brightness of the shadowed corners. You don’t need a brighter light; you need a wider distribution. We need to flood the zone with uniform lumens so that the brain stops trying to process the difference between “bright” and “pitch black” and simply sees “floor.”

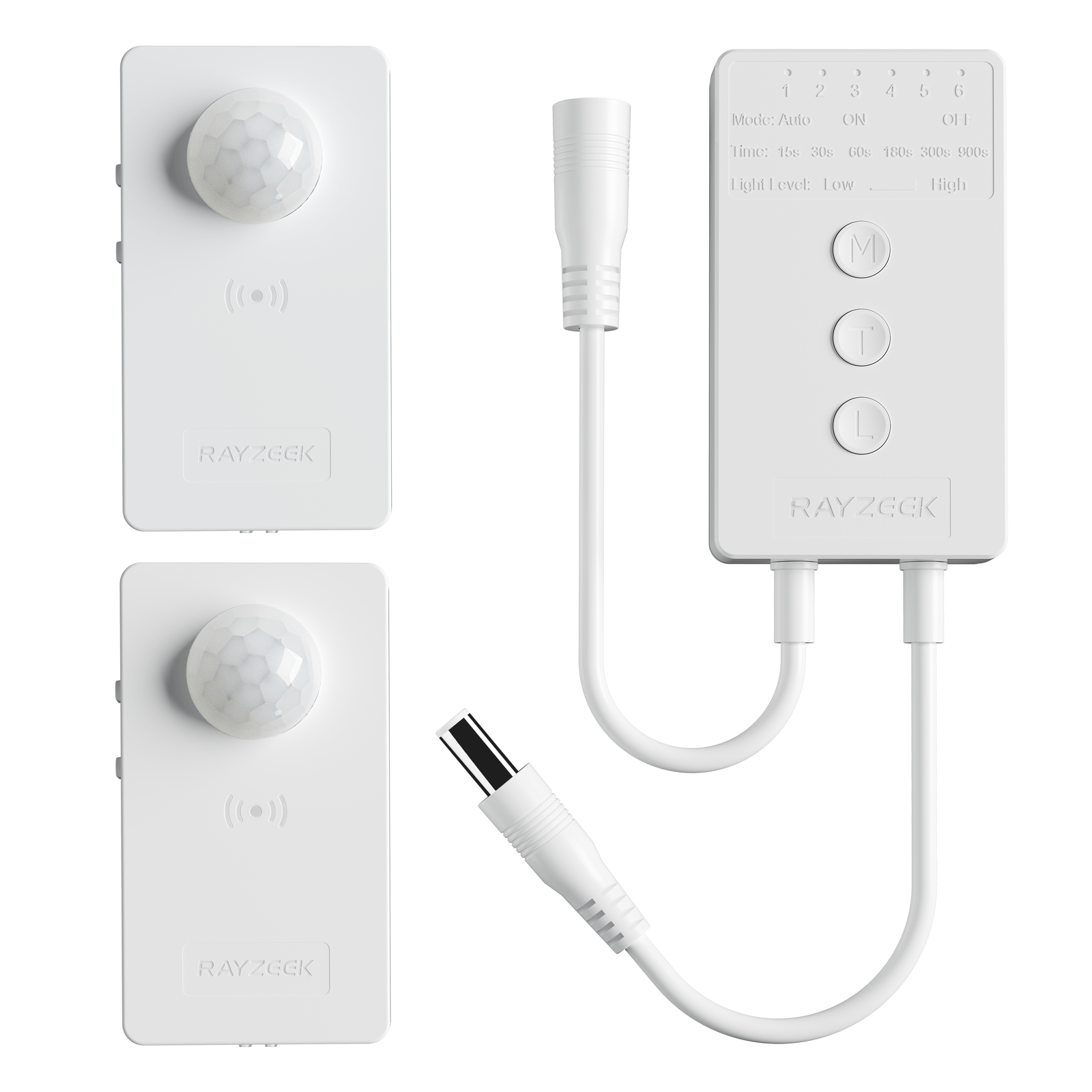

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

Why Smart Bulbs Are a Safety Hazard

There is a temptation to solve this problem by simply screwing a Wi-Fi enabled smart bulb into the existing socket. This is a critical error in safety architecture.

A smart bulb requires the wall switch to be left in the “on” position permanently to function. The moment a guest, a child, or a panic-stricken homeowner flips that toggle out of muscle memory, the “smart” system dies. You are left with a bulb that is chemically incapable of turning on, regardless of what your app or voice assistant says. Gravity does not care if your Wi-Fi mesh is rebooting or if the cloud server is down.

Furthermore, we have to consider the failure state. In the event of a power outage that is subsequently restored—say, at 3:00 AM after a thunderstorm—many generic Wi-Fi bulbs default to “On” at 100% brightness. The entire house wakes up because the basement is blazing. Conversely, if the internet cuts out, you lose control entirely. For safety-critical lighting like stairwells, the automation must happen at the switch, not the bulb. The switch is the only piece of hardware that respects the physical reality of the circuit.

If you are dealing with an older home—anything built before the mid-80s—you might be hesitating because you’ve opened up the switch box and found only two wires, missing the crucial “neutral” wire required by most smart switches. This is the “No Neutral” panic that stops most DIYers cold. But this is no longer a valid excuse. Modern RF-based dimmers, specifically the Lutron Caséta line (PD-6WCL), are engineered to operate without a neutral wire. They steal a microscopic amount of power through the bulb itself to stay alive. There is no need to rewire the house; you just need to buy the right hardware.

Maybe You Are Interested In

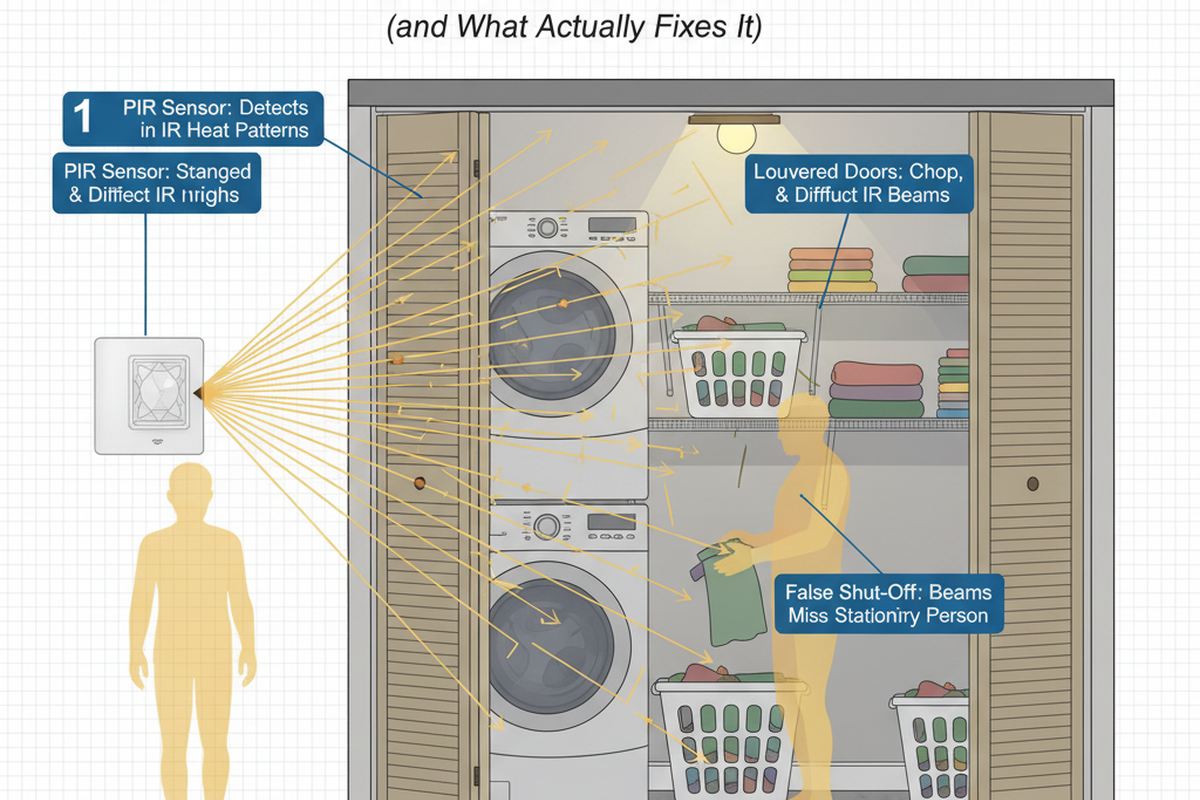

The Geometry of Detection

The goal is simple: the lights must be on before your foot leaves the top landing. To achieve this, we need to talk about sensor placement and the “Grocery Bag Simulation.”

Imagine you are carrying two full paper bags of groceries, or a laundry basket tucked under your chin. You approach the basement door. You cannot see the switch, and you certainly cannot reach it. If the lighting design requires you to put down the load to turn on the light, the design has failed. Here, automation stops being a luxury and becomes a functional requirement for safe transit.

The mistake most people make is placing a motion sensor near the floor or using a “nightlight” style plug-in sensor. These devices are practically useless for an approaching adult. A sensor near the floor sees a chaotic world of pets and ankles. It will trigger every time the cat walks by—which is the number one complaint we hear from new users—but it will often miss the torso of a human entering the stairwell until they are already on the first step. By then, the latency of the system means the light turns on after you have committed your weight to the descent. That 200-millisecond lag is where accidents happen.

Sensors must be mounted high—on the ceiling or high on the wall—where they can cast a wide infrared (PIR) cone that covers the approach vector. We want the sensor to “see” the heat signature of a person entering the “intention zone” three feet before the stairs begin. This is why battery-powered RF sensors are superior to hardwired wall switches for detection. You can stick a wireless sensor (like the Lutron Radio Powr Savr) in the exact geometric sweet spot on the ceiling to catch motion early, without needing to run a new romex cable through a finished ceiling. It separates the “trigger” from the “load,” allowing the physics of detection to dictate placement rather than the convenience of the electrician who wired the house in 1975.

Passive Infrared sensors detect heat differentials versus background radiation, so they need a clear line of sight to your body heat, not your feet. Aim them at the chest height of the approach.

The Retrofit Architecture

In a finished basement, the idea of running new wires to create a 3-way switch (one at the top, one at the bottom) involves cutting drywall, drilling through headers, and repainting. It is expensive and messy. This is why so many scary basements stay scary. The homeowner assumes the fix requires a licensed electrician to tear apart the walls. The reality is that we can solve this with wireless bonding in about fifteen minutes.

The strategy is straightforward: replace the single existing switch (usually at the top of the stairs) with a smart dimmer. Then, take a wireless remote—a Pico remote is the standard here—and mount it to the wall at the bottom of the stairs using a bracket that makes it look exactly like a hardwired switch. Bond the remote to the dimmer via a local radio frequency (Clear Connect), not Wi-Fi. Now, you have a 3-way switching solution without pulling a single inch of wire. The signal travels through the floor joists instantly.

A common objection here is battery anxiety. People worry about changing batteries in their light switches. But we aren’t talking about a AA battery that dies in six months. The coin cell batteries in these industrial-grade remotes are rated for ten years of typical use. You will likely replace the water heater before you replace the switch battery. It is a “set and forget” reliability that rivals copper wire.

There is also a lot of noise right now about “Matter” and “Thread” being the future of smart homes. That may be true for the tinkerer who wants their toaster to talk to their fridge. But for a safety circuit that prevents you from falling down stairs, we stick to proprietary, local RF (Radio Frequency) that has been stress-tested for decades. We don’t want the lights to fail because a firmware update on a hub went wrong.

Light Quality as a Safety Metric

Finally, once the automation is reliable, we must address the quality of the light itself. The “warm white” (2700K) bulbs that look cozy in a living room are often too dim and yellow for a utility stairwell. They soften edges and blend contrast, which is exactly what we don’t want when identifying the edge of a stair tread. For transit areas and basements, we want a cooler, cleaner light—something in the 3500K to 4000K range. This higher Kelvin temperature mimics daylight and increases visual acuity, making it easier for the eye to register the texture of the carpet or the toy left on the step.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

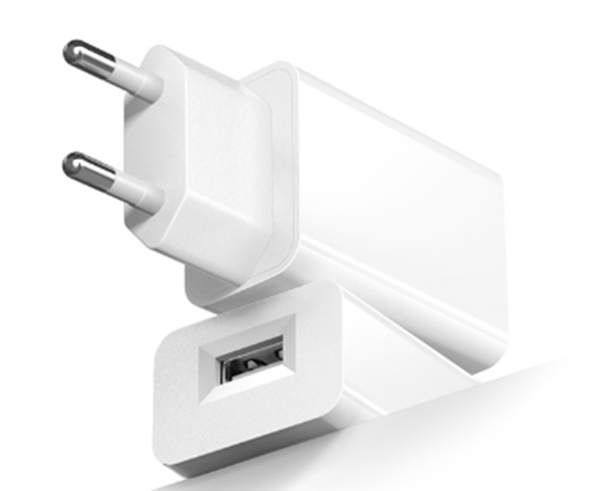

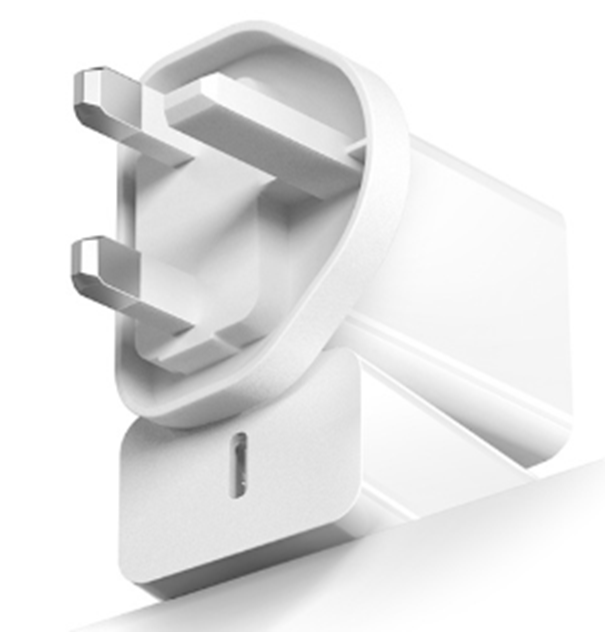

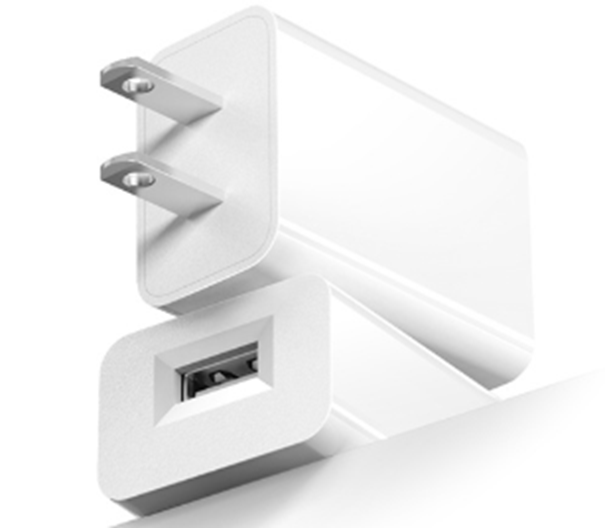

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

You do need to be careful with LED compatibility. Some older LEDs or cheap “bargain bin” bulbs will buzz audibly when paired with a smart dimmer. It’s an annoyance rather than a danger, but it drives people crazy. It’s worth checking the manufacturer’s compatibility tool or sticking to major brands to ensure the dimming curve is smooth and silent.

When you combine high-placement sensing, instant-on local control, and high-CRI (Color Rendering Index) lighting, the basement changes character. It stops being a dungeon you flee from and becomes just another room. The “Scary Factor” evaporates because the uncertainty is gone. You don’t have to be brave to go downstairs; you just have to be able to see.