The most dangerous room in a house isn’t the kitchen with its knives or the bathroom with its slippery tile. It’s the unconditioned attic—specifically the transition zone between the top rung of a ladder and the plywood decking.

This is where the physics of home maintenance works against the human body. You’re usually carrying something awkward: a box of holiday ornaments, a suitcase, or an HVAC filter. You’re balancing on a fiberglass Werner ladder that’s seen better days. And, crucially, you’re doing all of this in pitch darkness, reaching one hand up into the void to find a thin cotton string that may or may not still be attached to the fixture.

If that string has snapped, or if it’s swung up onto the rafters where you can’t reach it, the scenario shifts from “annoying” to “medically significant.” The instinct is to climb one rung higher than the safety sticker allows, lean out past your center of gravity, and try to unscrew the hot bulb to check the connection. This is the moment gravity wins.

In utility spaces, passive safety must always beat active safety. Active safety requires a human to perform an action—pull a chain, flip a switch, launch an app—while under duress. Passive safety happens automatically. In an attic, the light must be on before your torso clears the hatch. If you’re relying on a pull chain in 2024, you’re trusting a failure mechanism that was outdated thirty years ago.

The False Economy of Batteries

When homeowners realize the danger of the dark attic, their first impulse is often to buy a pack of stick-on motion lights. They’re cheap, they claim to be “install-anywhere,” and they require no interaction with high-voltage wiring. Don’t fall for it.

Battery-operated devices aren’t infrastructure. They’re maintenance debt. In the conditioned air of a hallway, a battery puck might last six months. In an uninsulated attic, where ambient temperatures in the Mid-Atlantic can hit 135°F in July and drop to 15°F in January, batteries are doomed. The heat degrades the chemical lattice inside alkaline cells, causing them to leak acid. The thermal cycling melts the cheap adhesive backing, so when you pop the hatch six months later, you find your safety lights lying face down in the fiberglass insulation, dead.

Then there’s the “Smart Home” temptation—screwing in a Philips Hue or a Wi-Fi enabled bulb. This fails the grandmother test, and it fails the physics test. First, Wi-Fi signals struggle to penetrate the foil radiant barriers and dense lumber of an attic floor. Second, smart bulbs require the wall switch or pull chain to remain “ON” forever. The moment a helpful relative or contractor flips the switch off, your automation is dead, and you’re back to climbing a ladder in the dark to reset a bridge. If a safety device requires an app to function, it’s not a safety device. It’s a toy.

Maybe You Are Interested In

The only viable power source for an attic light is the 120V mains electricity already running to the junction box. It doesn’t care about heat, it doesn’t leak acid, and it doesn’t run out.

The Zero-Wiring Retrofit

For decades, the only way to get motion-activated lighting in an attic was to hire an electrician to rip out the porcelain keyless fixture (the standard white bulb holder) and wire in a new commercial-grade sensor unit. That costs $300 in labor for a $40 part. Most people just risk the ladder instead.

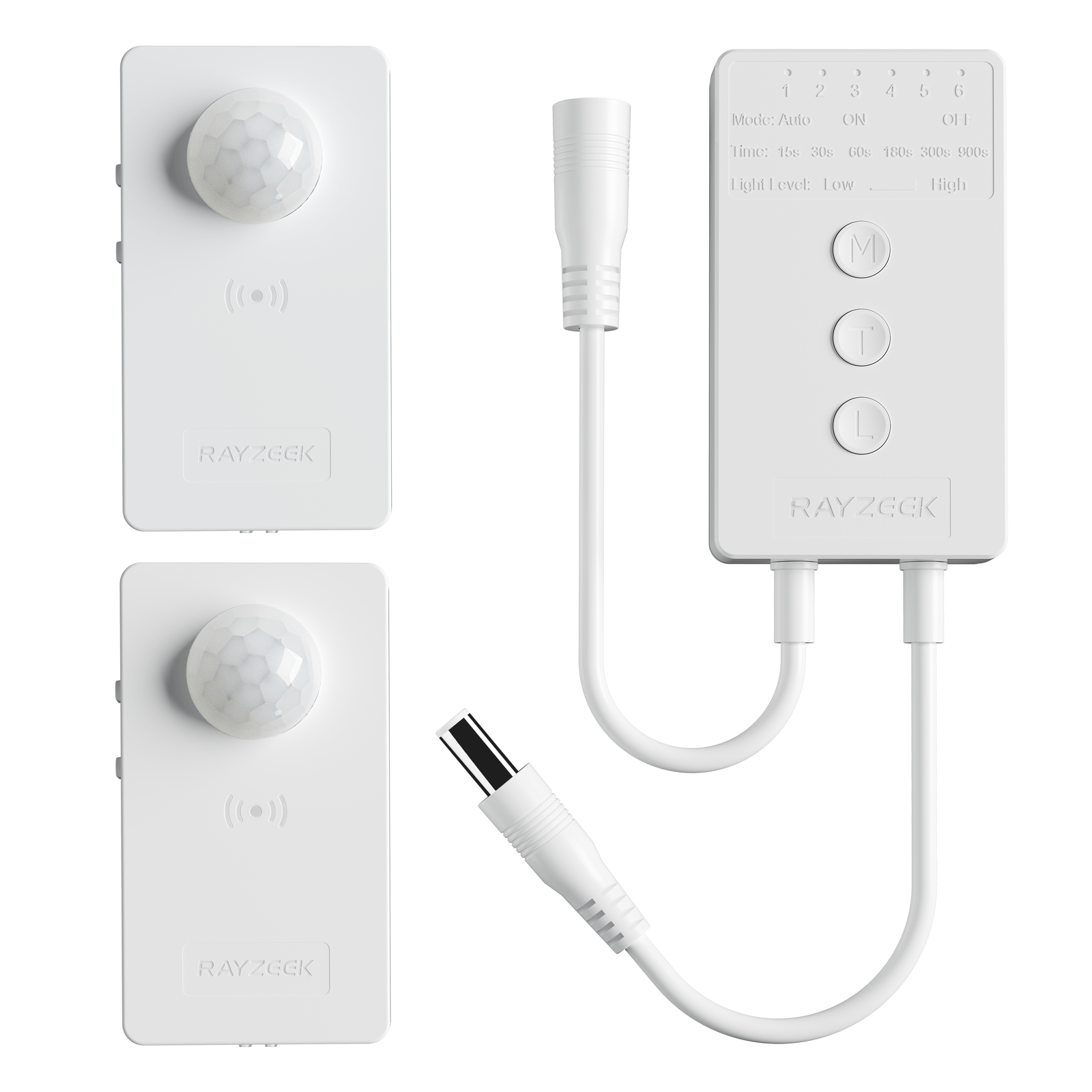

The solution that bridges this gap is the screw-in motion sensor adapter, specifically units like the Rayzeek RZ021 or RZ022. They aren’t pretty. They look like bulky collars that sit between your lightbulb and the socket. But in an attic, aesthetics are irrelevant.

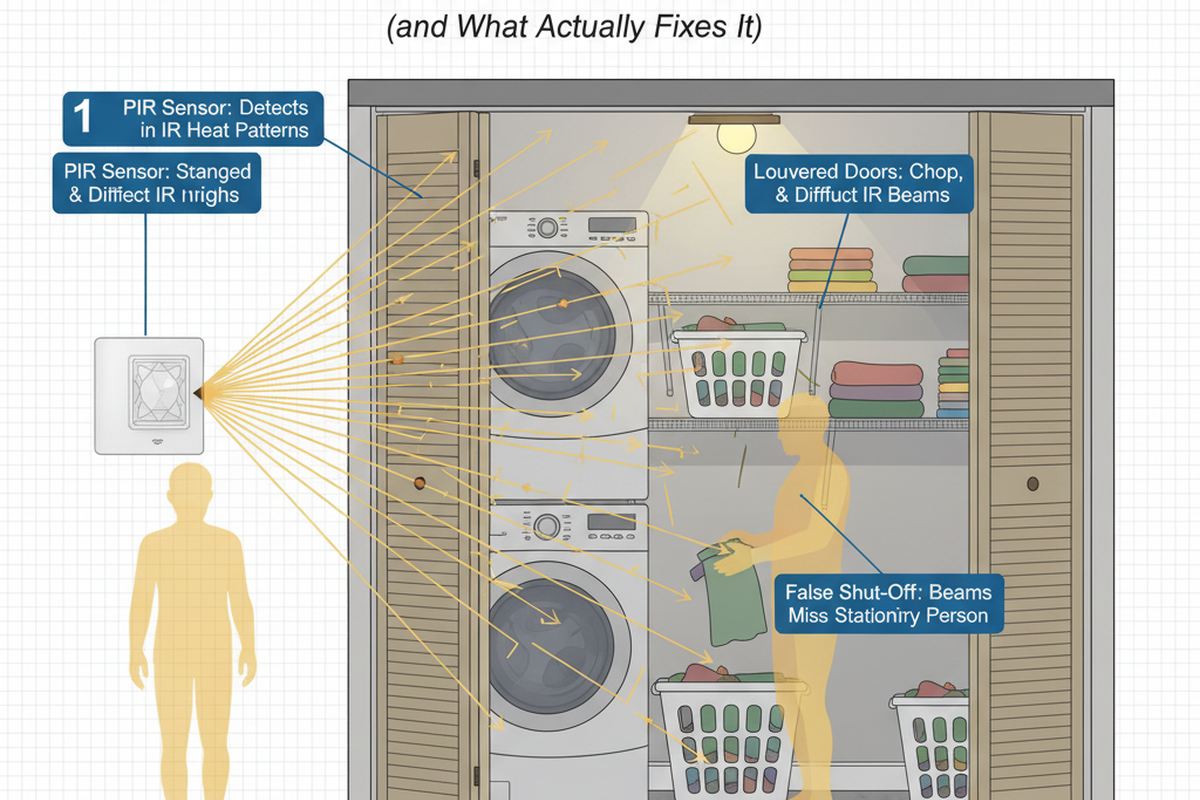

The mechanism is simple but robust. You unscrew your existing bulb. You screw the Rayzeek adapter into the E26 socket. You screw the bulb back into the adapter. That’s it. The adapter siphons power from the mains to run a PIR (Passive Infrared) sensor. When it detects heat signatures moving across its field of view, it closes the circuit and lights the bulb.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

This approach solves the “Broken String Panic” that plagues older homes. If your pull chain snapped off inside the housing three years ago, you don’t need to replace the entire fixture box—a job that scares many DIYers due to old, brittle insulation on the copper wires. As long as the internal switch mechanism is stuck in the “ON” position (or can be pulled once with pliers to stay on), the sensor takes over all switching duties. The pull chain becomes obsolete.

Thermal Dynamics and Sensor Logic

We specify a PIR sensor here rather than more modern radar or ultrasonic options for a reason: attics are hostile environments. A sensor needs to distinguish between a human entering the space and the natural shifting of the house.

PIR sensors work by detecting the difference between the background temperature and a moving heat source. There is a valid concern here: in the peak of summer, an attic can reach 100°F+, which is perilously close to human body temperature. In theory, this reduces the “contrast” the sensor sees, potentially leading to a failure to trigger. However, in practice, the motion component of the signal is usually strong enough to overcome the thermal noise, especially with the newer lenses used in the RZ series.

We aren’t talking about precision detection for a security system; we’re talking about blasting 1600 lumens into a dark void when a hatch opens. The Rayzeek units generally handle this thermal load better than integrated LED fixtures because the electronics are separated from the heat-generating diode of the bulb by the adapter body. Just ensure you use an LED bulb, not an incandescent. An old 100W incandescent produces massive waste heat that can cook the sensor sitting directly above it.

Installation Reality Checks

While this is a “screw-in” solution, there are physical constraints to check before you order. The adapter adds about 2 to 2.5 inches of length to the fixture. In a cramped attic with a low roof pitch, this might push the bulb dangerously close to a rafter or stored boxes.

You need to verify clearance. An LED bulb touching a cardboard box is a fire hazard, regardless of how it is switched. If your current bulb is already brushing against a truss, this solution won’t work without a smaller form-factor bulb.

Here are the three “pre-flight” checks:

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

- The Switch: Ensure the pull chain or wall switch controlling the fixture is ON. If the pull chain is broken in the OFF position, you’ll have to open the fixture to bypass the switch—at that point, call a pro if you aren’t comfortable with wire nuts.

- The Bulb: Use a standard A19 LED. Do not use a “smart” bulb in the sensor socket; the electronics will fight each other, resulting in strobing or failure.

- The Settings: These adapters usually have small dials for “Time” and “Lux.” Set “Time” to maximum (usually 5-10 minutes) so you aren’t plunged into darkness while searching for a suitcase. Set “Lux” (light sensitivity) to the “Sun” or “24H” setting, so it turns on even if daylight is leaking through a vent.

I’m intentionally skipping the instructions for replacing the entire porcelain junction box. While a clean, hardwired install is technically superior, the risk of a homeowner disturbing 1970s wiring insulation and creating a short is higher than the benefit. The adapter uses the existing, UL-listed footprint. Use what’s there.

The Cost of Injury

It’s easy to hesitate over spending $20 or $30 on a “gadget” for a room you visit twice a year. But this is bad math. You aren’t buying a light switch; you’re buying insurance against a fall.

An emergency room copay for a sprained ankle is often $250. An orthopedic surgery for a fractured hip or a torn rotator cuff—common injuries from ladder falls—can run into the tens of thousands, not to mention the months of rehab. The Rayzeek adapter costs less than a takeout dinner.

The goal is to ensure that when you climb that ladder, your focus is entirely on your footing and your load, not on wrestling with a piece of cotton string in the dark. The light should be waiting for you.