For anyone who shares their home with an animal, the promise of a “pet-immune” motion sensor feels like a straightforward solution to a complex problem. The goal is simple: to detect an intruder without a cascade of false alarms triggered by a wandering dog or a climbing cat. But the language of “immunity” obscures a more complicated reality. It isn’t a feature you simply turn on; it is a carefully engineered compromise, a deliberate choice to make a sensor less sensitive in exchange for a quieter life.

Understanding this trade-off is the first step toward building a system that actually works. The marketing claim on the box, that a sensor “ignores pets up to 85 lbs,” is a fiction born from the sterile, predictable environment of a testing lab. It imagines a single object moving at a constant speed across an empty floor. It cannot account for the beautiful chaos of a real home, where a 15-pound cat leaping onto a sun-warmed countertop can appear, to the sensor, as the sudden arrival of a much larger threat. Nor can it account for two smaller dogs whose play combines their heat signatures into something the system interprets as a single, formidable presence. The weight rating is a guidepost, not a guarantee, and relying on it alone is the most common path to failure.

How a Sensor Perceives Heat, Motion, and Pets

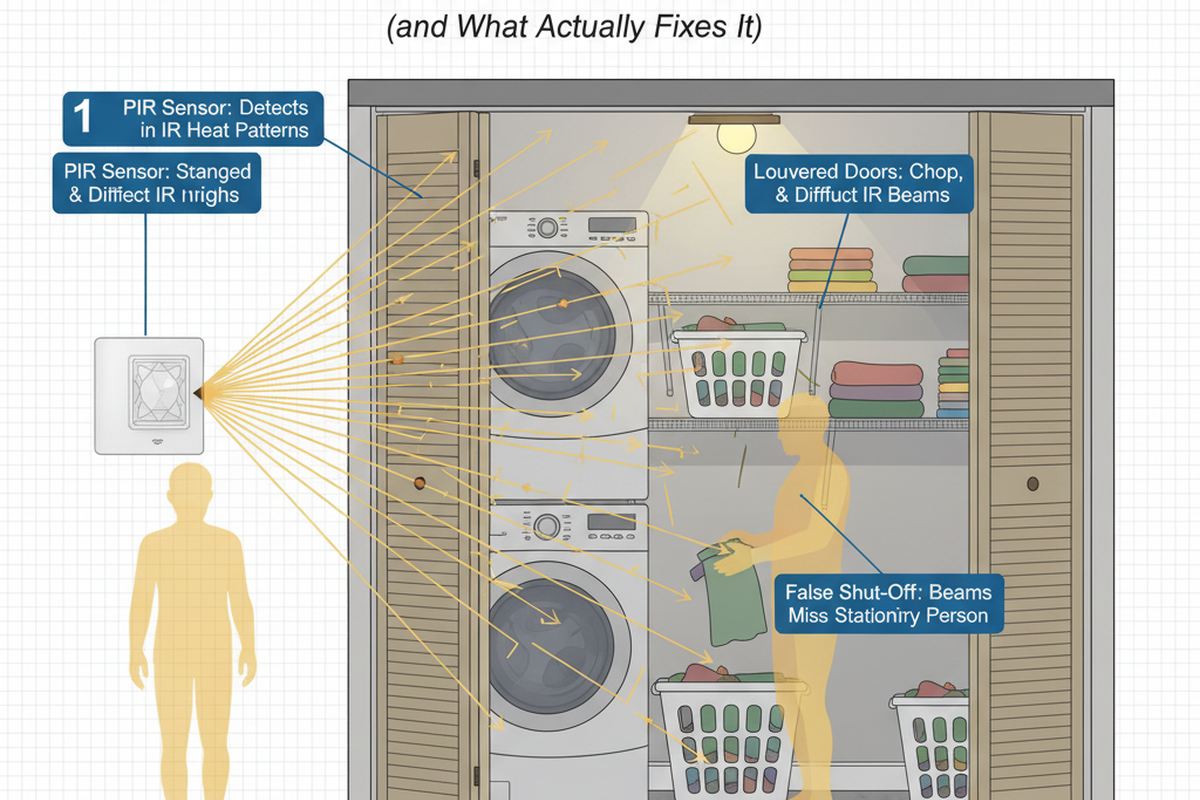

To grasp the limits of pet immunity, one must first understand how a Passive Infrared (PIR) sensor perceives a room. It is not a camera. It sees the world as a coarse mosaic of ambient heat. When a warm body moves across its field of view, it disturbs this thermal pattern, creating a rapid fluctuation that the sensor’s logic registers as motion. To a standard sensor, designed for maximum sensitivity, the heat signature of a Golden Retriever is functionally identical to that of a person. Both are significant thermal events that warrant an alert.

A pet-immune sensor attempts to add nuance to this black-and-white worldview. It achieves this primarily through a specialized lens that creates intentional blind spots, carving out a non-detection zone in the first few feet above the floor. Its internal logic is also more discerning. It may employ a “pulse count” system, requiring a moving heat source to cross multiple detection zones in a sequence that mimics the gait of a walking human. This more cautious logic is effective at filtering out the random movements of a pet on the floor. But this caution comes at a cost. The sensor may be marginally slower to react to truly erratic human movement, a subtle but real consequence of its programming.

Placement: The Strategy That Outperforms Technology

The conversation about motion detection often focuses too much on the hardware and not enough on the environment. The decision to invest in a specialized sensor often dissolves when you consider the power of intelligent placement. A standard, less expensive PIR sensor mounted at the recommended height of 7.5 feet and aimed correctly will naturally create what installers call a “pet alley”—a zone several feet wide along the wall beneath it where most pets can pass completely undetected by the sensor’s downward-looking gaze.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

This single strategic decision can provide more reliable security than a poorly installed pet-immune model aimed directly at a staircase or a favorite sofa. The objective is not to make your entire home immune to your pet, but to create monitored zones along the paths an intruder would most likely take. This is a goal often achieved with simpler hardware and a bit of forethought. You may find you need a pet-immune sensor only if your pet has free roam of a monitored area and is large enough, or acrobatic enough, to consistently enter those upper detection zones.

When the Compromise Fails: Large Dogs and Climbing Cats

There are situations, however, where the inherent compromises of PIR technology are pushed beyond their limits. A 120-pound Great Dane projects a thermal signature so substantial that it can overwhelm the filtering logic of even the highest-rated pet-immune sensor. It is, for all intents and purposes, indistinguishable from a human.

An even greater challenge is presented by cats. Their tendency to climb places them squarely in the detection zones engineered to spot people. To a sensor mounted in the corner of a room, a cat perched atop a tall bookshelf looks very much like the head and shoulders of a person stepping into view. In these scenarios, relying on a PIR-only solution, no matter how advanced, is an invitation for frustration. The problem is no longer one of sensitivity, but of fundamental technology.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

For these homes, the most robust solution is a dual-technology sensor. This device pairs a PIR sensor with a second, distinct method of detection, typically microwave (MW). The system’s logic requires both sensors to trigger simultaneously before sounding an alarm. A pet is warm and will trip the PIR. But most animals are not large or dense enough to return a significant microwave signal; a human body, being composed mostly of water, reflects that energy far more effectively. This dual-requirement acts as a powerful filter, virtually eliminating false alarms not just from pets, but from other common sources like billowing curtains or blasts of hot air from HVAC vents. It is the definitive choice for any space where reliability cannot be compromised.

The Final Considerations for a Reliable System

Even with the right hardware, long-term performance depends on environmental factors that are rarely discussed. The effectiveness of any PIR sensor hinges on the temperature difference between a moving body and its background. As a room’s ambient temperature approaches 98.6°F, in a sunroom on a summer afternoon, for instance, that critical difference shrinks. The sensor’s ability to “see” an intruder diminishes significantly, a powerful argument for using dual-technology sensors in any space with wide temperature swings.

This leaves one final, nagging question: could an intruder defeat a pet-immune sensor by crawling beneath its detection zones? While theoretically possible for someone with precise knowledge of the sensor’s placement and model, it is exceptionally difficult in practice. The lower blind zone is finite. As a person crawls across a room, their body will inevitably rise high enough to intersect one of the downward-angled detection beams. More importantly, a truly secure space is never reliant on a single device. It is a system, where overlapping fields of view from multiple sensors ensure that one sensor’s weakness is covered by another’s strength.