For the owner of a multi-tenant office building, new technology always arrives as a financial question. An investment in occupancy sensors is no different. The proposition seems simple enough—a promise of reduced energy waste by automating lights and HVAC systems. Yet, beneath this apparent simplicity lies a complex decision, where a hastily drawn projection can become a costly mistake and a thoughtful analysis can unlock value far beyond the utility bill.

The conversation about sensors is often framed around saving electricity. But that’s only the beginning of the story. The real calculation forces a decision about what a building is for. Is it merely a container of spaces to be managed for efficiency, or is it a dynamic system whose patterns, once understood, can be guided toward greater value?

The Two Paths of Automation

Before a single dollar is tallied, a building owner stands at a fork in the road. The choice made here defines the entire scope of the project, shaping not only the costs but the very nature of the expected return. One path is tactical, a direct assault on waste. It involves installing standalone sensors in specific rooms, a localized solution for a localized problem. The investment is contained, the installation straightforward, and the return is measured in the clean, unambiguous language of kilowatt-hours saved. It is a sensible, conservative approach, well-suited for targeting the most obvious pockets of inefficiency.

The other path is strategic. It treats the building not as a collection of rooms, but as an ecosystem of human activity. This approach involves a networked system where sensors do more than just trigger a switch; they communicate. They feed a constant stream of information about how and when spaces are actually used into a central platform. The upfront investment is undeniably greater, encompassing gateways, software, and the technical expertise to weave it all into the building’s digital fabric. The return, however, transcends simple energy savings. It becomes about information. And in modern real estate, information is its own form of currency.

The Anatomy of the Real Cost

With a path chosen, the analysis turns to the numbers, guided by the classic formula for return on investment. But the integrity of that formula hinges entirely on the honesty of its inputs. The “Total Cost of Investment” is where optimistic projections first begin to unravel. The price on the sensor’s box is only the first line item in a much longer, more complicated story of expenses.

The cost of hardware is deceptive. The sensors themselves, along with their necessary power packs and controllers, are just the tangible starting point. The true cost emerges in the labor required to make them functional. An installer charging by the hour in a building with complex ceiling plenums and after-hours work requirements can easily double the initial hardware estimate. Then comes the commissioning. This is the critical, often underestimated, expense of having a technician meticulously program the system—setting timeouts, defining zones, and ensuring the technology performs as a cohesive whole rather than a collection of disjointed parts. For a networked system, this isn’t an optional tune-up; it is the fundamental step that turns a box of electronics into a functioning intelligence platform.

Looking For Motion-Activated Energy-Saving Solutions?

Contact us for complete PIR motion sensors, motion-activated energy-saving products, motion sensor switches, and Occupancy/Vacancy commercial solutions.

Uncovering the True Return

Just as costs hide in the nuance of installation, the financial gains reveal themselves in layers. The most immediate return, and the one that justifies most projects, is the direct reduction of energy consumption. The calculation itself is straightforward. One can multiply the wattage of a light fixture by the hours it will now be off, factor in the days of operation and the cost of electricity, and arrive at a tidy annual savings figure. A 100-watt fixture, turned off for an extra four hours a day, might save fifteen or sixteen dollars a year.

But projections are clean, and buildings are messy. The most common error in these calculations is a profound optimism about human behavior. Theoretical savings assume an empty room, but reality is filled with cleaning crews, early arrivals, and manual overrides. A more truthful forecast begins with the ideal calculation and then discounts it by a “real-world factor,” a conservative hedge of 25 or 30 percent. This isn’t pessimism; it’s the hard-won wisdom of experience, creating a defensible number that can actually be achieved.

Get Inspired by Rayzeek Motion Sensor Portfolios.

Doesn't find what you want? Don't worry. There are always alternate ways to solve your problems. Maybe one of our portfolios can help.

The real story, however, begins when the system stops being about turning lights off and starts being about revealing how the building actually lives. For a networked system, the stream of occupancy data is where the strategic return is found, and it can dwarf the energy savings. Imagine the data reveals that a block of ten conference rooms never sees more than six used at once, even during peak hours. This is no longer an abstract statistic. It is a data-driven mandate to act. Converting just two of those underutilized rooms into leasable private offices can generate a revenue stream that makes the entire project’s energy savings look like a rounding error. The ROI, in this light, is no longer just about efficiency; it’s about creating new inventory from thin air.

The Liabilities Hidden in the Spreadsheet

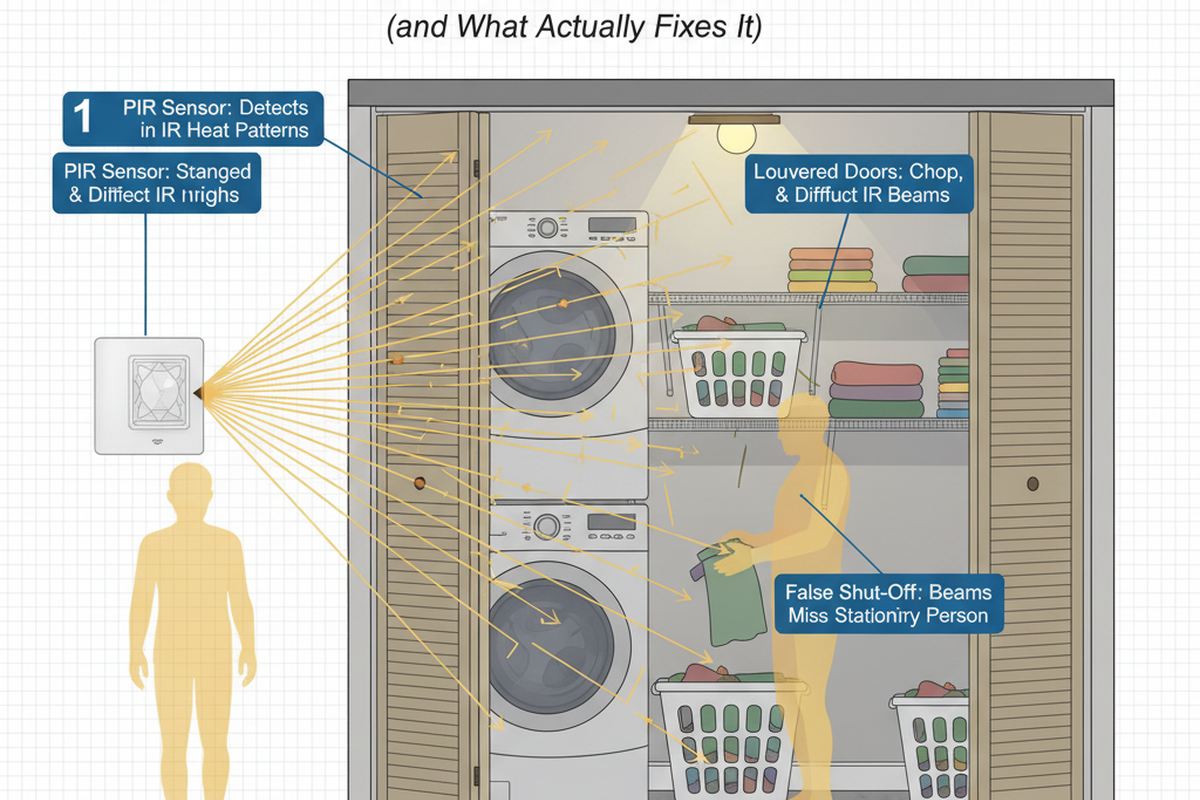

Yet, no financial model can account for the most significant risk of all: tenant frustration. The greatest threat to a sensor project’s success is not a faulty wire or an optimistic projection, but the quiet annoyance of a person whose lights go out while they are sitting perfectly still at their desk. This is not a minor inconvenience. It is a financial threat. The cost of a key tenant choosing not to renew their lease, citing persistent irritation with the building’s basic functions, is catastrophic compared to any conceivable energy savings. In that scenario, the project’s ROI becomes profoundly negative. The small, additional investment in superior dual-technology sensors for quiet spaces, or in the professional commissioning that ensures appropriate time delays, is not an upsell. It is an insurance policy against a failure in the core business of keeping tenants satisfied.

This is why the seductive simplicity of the “Simple Payback Period” is such a dangerous shortcut. It is tempting to divide the total investment by the annual savings and arrive at a single, digestible number—a 2.5-year payback. But this metric is blind. It sees no difference between a cheap system that pays for itself in two years and fails in the third, and a robust system that takes four years to pay back but delivers reliable performance for fifteen. The true financial health of an asset is not measured by how quickly it recoups its cost, but by the total value it generates over its entire functional life. The real calculation demands we look past the easy numbers and ask the harder, more important questions about long-term value and reliability.